While I jokingly said to my striking colleagues that as an ADR professor I was excited by the strike, I was usually met with looks of shock and dismay. I quickly learned not to speak so excitedly about the strike’s’ similarities to my ADR content because I was quite alone in my enthusiasm.

Within the first few weeks of the fall 2017 semester, I provided my students with a document called The Appropriate Dispute Resolution Continuum. Note the difference between the two titles, Alternative Dispute Resolution and Appropriate Dispute Resolution. Many Dispute Resolution practitioners believe that the word “alternative” should be dropped from the term as Dispute Resolution is no longer considered an alternative but is now main stream. Therefore, appropriate dispute resolution connotes a choice in dispute resolution options.

The continuum looks at a simple dispute. First, when a conflict is discovered, parties can simply choose to ignore it. If they decide not to ignore it, they move to negotiation (two parties addressing the conflict themselves), mediation (the intervention of a neutral third party), mediation-arbitration (a process whereby a neutral mediator may switch hats and make a decision), arbitration (a quasi-judicial process where a decision is made), and finally adjudication which has a definitive “you win, you lose” outcome. The continuum also demonstrates who has the power to resolve the dispute. Clearly, there is more power for the parties to arrive at a mutual resolution during negotiation and mediation. As they move along the horizontal continuum, parties lose power as they head towards mediation arbitration, arbitration, court, and other power-based resolutions such as strikes, lockouts, or military coups.

It was not difficult to look at the strike and think immediately of that continuum. For example, my first class addressed positional negotiation with a simple exercise of two parties negotiating over a can of Alphagetti. “I want to pay this price” versus “I want this remuneration.” During the five week strike negotiations, it was not much different: “I want to pay this price, versus I want this remuneration,” however, it was on a much larger scale and involved many more people. While “I want this” versus “I want that” is inherent in all of us, it does not address a more sophisticated method of negotiation which involves why we want to buy at this price or sell at that price. Focussing on the why is called an interest based method of resolving a dispute. “A position is what you want and an interest is why you want it.” 1 Mediation is interest based; a neutral third party assists the parties to resolve a dispute on their own, focussing on their interests rather than their positions.

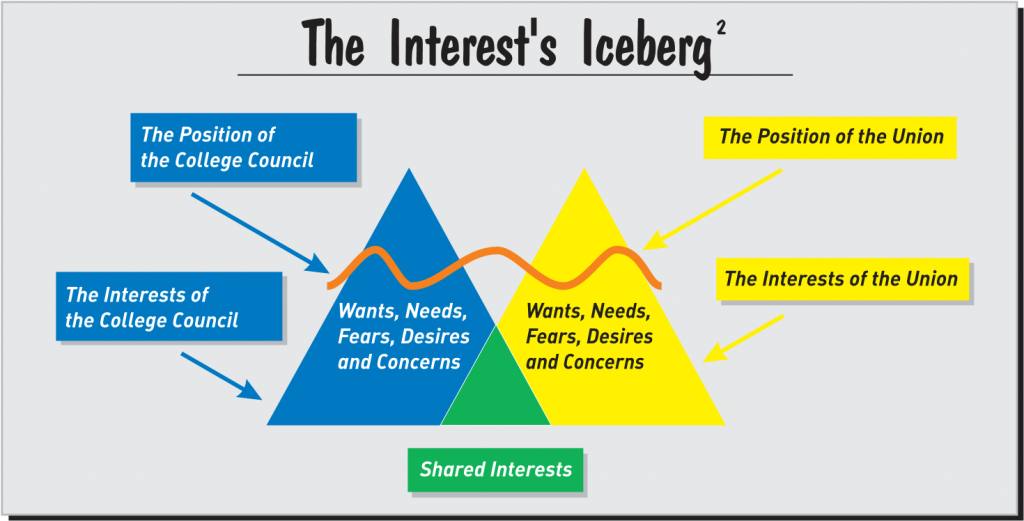

A position is quite clear; “I’m right and you are wrong.” Interests are; wants, needs, fears, desires and concerns (or a combination of those) that have not been met. Thus, in mediation, a party may begin entrenched in her/his position because (unknown to the other party) the party wants, needs or fears something. The two triangles represent the two parties in dispute. The two areas that overlap (green) depict the areas that are common between them. Looking at the college strike through this lens, the first pair of triangles represents the College Council (blue) and the Union (yellow). The colleges’ position was, “No, you’re not getting that!” The Union’s position was “Yes, we are!” The overlapping area (green) was maintaining quality education. So, while the parties have different positions, they have the same interest in quality education. A resolution may be found based upon that agree upon statement alone.

During the strike, the province of Ontario witnessed a mediator who was unable to move the parties off their positions towards a resolution. Since the mediation process failed, the next option on the continuum would have been mediation-arbitration, or med-arb. While this might have been a bit of a head scratcher for students (how does someone neutral suddenly become a decision-maker), this very option was introduced in Bill 178, Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology Labour Dispute Resolution Act, 2017 on November 19th, 2017; 11 (1) On or before the fifth day after this Act receives Royal Assent, the parties shall jointly appoint the mediator-arbitrator referred to in section 10 and shall forthwith notify the Minister of the name and address of the person appointed. Furthermore, Bill 178, Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology Labour Dispute Resolution Act, 2017 section 12(1) provides: The mediator-arbitrator has exclusive jurisdiction to determine all matters that he or she considers necessary to conclude a new collective agreement.

As a result of section 12(1), an appointed mediator-arbitrator mandated full and contract faculty back to work with a new collective agreement that saw advancement for job security, partial load faculty (unionized contract faculty), and the ability to grieve for more full-time positions. It also provided a provincial taskforce to address issues important to the strike such as the precarious worker, faculty numbers, and other key elements.

In class, we discussed the next and more adversarial processes on the continuum, namely arbitration, litigation, and other power-based methods. The strike was without a doubt an example of a power-based method of resolving a dispute and subsequently created emotional and financial impacts on students, faculty, counselors, librarians, college facilities, administrators, parents, friends, family, the local economy, and the government. While the strike lasted for five weeks, the impact far exceeded its duration and it would be many months before the dust settled and a sense of normalcy returned to college life. When the strike did end and we returned to college, things felt undone for the first little while. This led us to contemplate another area of our ADR syllabus, namely Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement, or BATNA, as it is commonly referred to, or as one student aptly suggested, a BATNA prepares us if we are unsuccessful in a negotiation setting. Unfortunately, in June 2018, there was no BATNA for the new Provincial Government disbanding the taskforce leaving many of the significant issues unanswered and full and contract faculty wondering what they went on strike for.

There were many ways that the fall 2017 Ontario college strike caused stress for many people. However, the strike also demonstrated key ADR concepts that students could learn from. I hope some of my students said, “Hey, didn’t we talk about something like that in class?”, or “Isn’t what is going on right now an ADR thing?”

On my first day back in class I said to my students, “While we can agree to disagree, we cannot agree to be disagreeable.” Then we debriefed the strike and its similarity to my ADR content. My students were less than enthusiastic; they wanted to put the past behind them, move on with their studies, and wrap up the delayed semester. While I was still excited about the similarities, I was pretty much alone with my enthusiasm once again.

1 (2011). Retrieved 2018, from www.airuniversity.af.mil: https://www.airuniversity.af.mil/Portals/10/AFNC/documents/pdf/pracguide2011.pdf

2 Unknown.(2015). https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com. Retrieved from https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/ blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/8/11350/files/2015/04/Mediator-Iceberg-11m54g1.pdf